With the consolidation of the Saudi state starting in the 1960s, the regime has progressively imposed unified dress codes for Saudi men and women, that for the latter has meant wearing a long, black cloak [‘abaya] and veiling. Various state institutions, like schools, universities, and the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice—commonly referred to as the “morality police” or “mutawi‘a”—have increasingly rigorously monitored women’s strict dress codes, on which much has been written (Le Renard, 2011, 2014, Al-Rasheed, 2013). This essay deals with a different relation of power that has received less attention. It shows how the Saudi regime is currently engaged in seemingly contradictory selective practices of “unveiling” Saudi women. On the one hand, unveiling Saudi women entails publicly displaying successful, unveiled Saudi women—who the regime constructs as “exceptional women”—to the world as a communication strategy in which foreign, especially European and North American, media are often complicit. On the other hand, this unveiling is rooted in heightened state surveillance of the population, which requires the identification of Saudi citizens, a practice that is incompatible with women covering their faces.[1] Far from attempting to “liberate” women by unveiling them, as simplistic liberal understandings of veiling would have us believe, the Saudi state is actually extending its control over Saudi subjects through these selective practices of unveiling, a process in which foreign media, which often reproduce these representations of "exceptional" women, play an important part.

Unveiling as Showing: Western Media and the Saudi State

Visual representations of Saudi women in European and North American media carefully select the women that are shown.[2] In general, photos show women for whom it is not a problem to have one’s face photographed and published—a small minority, especially in the capital, Riyadh, where most Saudi women cover their faces when in the company of men who are not close relatives. Photos often showcase those Saudi women with educated, liberal, and wealthy backgrounds, who also tend to be public figures.[3] The idea is to counter the invisibility that the veil supposedly imposes on Saudi women and to herald their personalities and activities. This approach, however, has the effect of actually limiting the visibility of Saudi women by producing a homogenous category of “Saudi woman,” ignoring, in particular, women with other class backgrounds and political orientations—not to mention non-national residents who make up about one third of Riyadh and Jeddah`s inhabitants, and one fourth of the country`s total population.

In reproducing official visual politics, these media outlets participate in the Saudi regime’s policy to put forward "exceptional women" as part of an effort to improve the country`s image (Al Rasheed, 2013). In the aftermath of the attacks of 11 September 2001, official visits abroad have often included delegations of Saudi women who were active in economic and intellectual fields, and shared the characteristic of not covering their faces. These women were used to counter global stereotypes of Saudi women as secluded, uneducated, and oppressed. They were also supposed to present a "human" face for a country often described as obscurantist, theocratic, and closed. As such, the regime makes it easy, and permissible, for journalists and photographers staying for short periods in the kingdom to contact these prominent women, since "fixers" already know them and have their contact information.

In both foreign media as well as official government business, women are portrayed as the one-dimensional category of Saudi women, devoid of other markers of belonging. The very presence and visibility of selective women’s bodies is intended to herald and represent the ostensibly progressive social transformations in Saudi Arabia. However, Western media have their own logics and interests, which transcend the public relations policies of the Saudi regime. These media tend to objectify Saudi women in specific ways. Commentaries as well as photo captions of visual representations of "exceptional women” stress particular notions of body and dress. The French daily newspaper Liberation, for example, published a biographical essay of filmmaker Haifa al-Mansour titled, "Haifa Al Mansour, wearing jeans and unveiled" [Haifa Al Mansour, en jeans et sans voile]. Al-Mansour, who is one of the few Saudi filmmakers to achieve such global success and whose film Wadjda won the 2014 BAFTA Award, cannot be appreciated beyond her not wearing the veil. While media portrayals tend to obsess about physical appearance whenever they deal with women in general, this particular focus on the veil, or rather the lack thereof, resonates with a colonial and imperial willingness to “unveil” women in Muslim societies (Ahmed, 1992; Abu-Lughod, 1998) in a specific way: while the educated, “liberal” women are not necessarily exoticized as traditional or tribal anymore, they nevertheless continue to be represented in ways that objectify them, reducing them to a set of evaluations of their appearance—what they wear, how they smile, what hairstyle they choose.

Beyond the fixation on “exceptional” women, those few supposedly enlightened Saudi women, European and North American media tend to depict all other women in the country, especially those wearing the niqab, as passive, having no agency. The resonance of these images of women in niqab with colonial so-called harem fantasies is even more obvious since they are shown as both secluded victims and freaks—sometimes even sexual deviants.[4] In two caricatures of the so-called “women-only city,” which in fact is a business district, the women are shown as secluded, bored, oversexualized, and, overall, lacking men: it reveals much about postcolonial fantasies of Saudi women shaped by racist representations and heterosexist norms.[5] More generally, the representations often focus on what “imperial eyes” (Pratt, 2007) see as “taboo,” “paradox,” and/or “hypocrisy” in relation to sexuality. For instance, a documentary broadcasted on a private television channel focused on Saudi women and the market for lingerie. The thread was the supposed “paradox” between the high consumption of underwear and women’s public dress code.[6] The identification of such “paradoxes” is telling of the norms and hierarchies—especially the stigmatization of veiled Muslim women—in the societies that (re)produce these representations. To return to the documentary, the "paradox" in question is that veiled (Saudi) women—who can only be read as conservative, backwards, oppressed—wear sexy lingerie. Here, veiled women are treated as freaks, whose intimate practices are scrutinized and described as incoherent, weird, and deviant. The implicit message is that "normal" women are not veiled, and that veiled women should not wear sexy underwear identified with a certain vision of “liberated” sexuality. The fact they do is treated as bizarre and erotic. This kind of representation of Saudi women tells much about gender and race hierarchies, and about the racialization of “Muslim women” in particular, in the societies that produce them. They contribute to dehumanizing women wearing niqab.

Unveiling as Surveillance

Alongside its diplomatic use of “exceptional women,” the Saudi regime has developed a surveillance-oriented policy of “unveiling Saudi women.” Following 11 September 2001, and the subsequent attacks inside Saudi Arabia, the regime launched an intense and violent anti-terrorist campaign across the country. Under the umbrella of anti-terrorism, which in reality targeted many forms of anti-regime activism, the regime reinforced state security and surveillance. Modernizing bureaucratic practices that enabled a more efficient monitoring of the population, such as means of identification, was also central to these efforts. Saudi women were first allowed to have their own personal IDs, which included photographs, in 2002, and in 2013, they became mandatory for all Saudi women within a period of seven years. Before 2002, all female citizens were listed on their legal guardian`s card, without a photo. A legal guardian can be the father, the brother, the husband, or the uncle, depending on the woman’s status and situation. The photos of Saudi men and both non-Saudi men and women, in contrast, have been included on IDs, visas, and residence cards for a long time. The reason for not including photos of Saudi women with their faces showing was not stated officially. However, for decades the Council of Senior Scholars [ulama], a state institution, has defined women’s faces as ‘awra [a body part not to be shown] and recommended that women cover their faces in front of male “strangers.” According to the young women I met in Riyadh during fieldwork, this principle was widely shared among Riyadh’s Saudi inhabitants, even though it was not necessarily justified in religious terms. Wearing the niqab can also be considered a “Saudi family” practice, one that promotes respectability and distinguishes national from non-national women.

Personal IDs make women’s daily bureaucratic dealings easier and prevents impersonations in cases of intra-familial conflict brought in front of the court.[7] The other side of the coin, however, is that authorities can now readily identify women. A November 2012 decision by the Consultative Council [Majlis al-Shura], an assembly whose members are appointed, further stated that Saudi women would also have to reveal their faces for security checks before male inspectors if needed. Here, image participates in a broader process through which the relationship between the state and Saudi women becomes increasingly direct by bypassing the mediating male family members, whose presence, however, remains compulsory for many procedures. This is an ambivalent process, as it both opens new opportunities to women while subjecting them to closer state control (Le Renard, 2014). The process of unveiling as surveillance is not specific to the Saudi state, as is evident in the debates around forbidding niqab or "integral veil" in many European countries as well as Canada. So far, France is the only country that has passed such a law. Following a controversy on niqab and a 2009 decree forbidding balaclavas in demonstrations, a 2010 French law banned covering one’s face in all public spaces. The possibility of identifying faces has become an essential aspect of state power and the Saudi state is not exceptional in this regard.

In Saudi Arabia, heightened surveillance practices that rely upon such mundane bureaucratic measures as making women’s faces legible are a considerable change, all the more so given that taking and producing photographs and images of women in public is not permitted. It is forbidden to take photos in many public spaces, such as shopping malls, streets, and around “compounds,” the gated communities largely inhabited by rich expatriates. These are monitored by hi-tech security cameras and are often off-limits to Saudis. It is also forbidden to take photos in for-women-only spaces—such as women’s campuses and schools, some workplaces, religious spaces, and many commercial spaces—but for different reasons. A lot of Saudi women in Riyadh try to prevent any circulation of photographs in which their faces appear, for complex and diverse reasons that deal with modesty, respectability, family values, and/or religious beliefs. On Saudi websites representing women’s institutions, photos generally show empty courtyards and meeting rooms, and in general, there are no security cameras inside for-women-only spaces, probably to prevent the possibility of images being leaked. In the 2000s, the regime criminalized the circulation of photos or videos of non-consenting Saudi women, as well as the blackmailing of women with photos or videos representing them, evidenced by the increasing arrests of the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice and several judgments in courts. (Le Renard, 2011: 137-139).

While the universalizing of state recognitive practices (photo IDs, for example) may be seen as a move towards the ungendering of citizenship, this should more importantly be understood as a more invasive extension of the Saudi state into the lives of its subjects—both as the arbiter of these practices—deciding when, how, and why women’s photographs may be taken and in what forms they may circulate—and as the power behind new forms of surveillance.

Escaping Control?

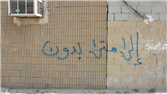

During extended periods of research in Riyadh between 2006 and 2009, the young women I worked with often showed their personal photos wherein their faces appeared, such as wedding photos, but they did not give or send them to other people beyond their close relatives. However, anonymous photographs considered as "fun" and provocative were widely circulated between mobile phones through Bluetooth. Many were of women, often in groups, wearing niqab; in other words, they were not identifiable. In the photographs, women adopted unusual poses such as drinking whisky from the bottle, or performing model-like positions in a fast-food "family corner." These images subverted several power relations shaping official representations of Saudi women: not only did they blatantly transgress norms of respectability that construct the figures of “exceptional women” in the regime’s communication policy, but they also escaped surveillance by maintaining their anonymity.

The resistance to Saudi state control over photography and filming extends far beyond the politics of self-representation. In recent years, the dissemination of images, through the use of smartphones and social media platforms, has been a key component of activism in a country where any demonstration is forbidden, as reaffirmed and demonstrated by the advent of these protest movements, both in Saudi Arabia and in neighboring countries. Videos of altercations with police and of diverse forms of protests were posted on YouTube and circulated widely, especially those of the largest demonstrations in the Eastern Province, attended by both men and women, and which were violently suppressed. These videos suggest how the ability to recognize or be recognized, to maintain anonymity and to undermine it—for both state actors and citizens—is complexly situated within relations of power.

This was the case, for instance, with flash protests by groups of Saudi women since 2011, especially in Riyadh and Buraidah, against the detention without judgment of thousands of people suspected of being linked to “terrorist networks.” Some of these protests led to arrests. In 2012 in Abha, the capital of Asir Province in the south of Saudi Arabia, female student protests against the poor learning conditions and the disrespectful university administration were violently suppressed by an assemblage of state security forces, including security guards, civil police, and the morality police. Fifty-three students were injured and, according to some sources, one died. Videos served as testimony both to the collective power of the women involved in these political acts and to the violence of the state in the suppression of these protest. As if to avert the disruptive capacity of these images, the videos have since been removed.[8]

Activism of another form—the Women2Drive campaign—has consisted of actions conducted individually, filmed, and posted on YouTube. In Spring 2011, several Saudi women activists called on women to drive themselves to their daily destinations and, if possible, to post videos of themselves doing so. The police responded to the campaign by arresting women who were caught driving, releasing them several hours later. The most visible activist involved in the campaign, Manal al-Sharif, who posted videos that explained the campaign and showed her driving, with her face intentionally recognizable, spent ten days in prison.

Circulation and invisibility of alternative images

In response to the subversive use of images and videos, the Saudi state has worked to consolidate its surveillance capacity by suppressing web activism[9] and placing more restrictions on social media, video-sharing websites, and mobile phone uses.[10] Beyond these official forms of censorship, however, foreign, particularly European and North American, media play an important role in limiting the dissemination of certain forms of subversive imagery. Rather than simply parroting the communication strategy of the Saudi regime of promoting “exceptional” women, foreign media often highlight the narrative of the "rebel Saudi woman." Videos showing individual Saudi women speaking out for women’s rights are often picked up and circulated, as in the case of Manal al-Sharif, who became an internationally recognized figure. In another video that circulated internationally, a Saudi woman filmed the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (the “morality police”) as she reprimanded them after they reproached her for wearing nail polish. In contrast, images of women`s collective protests in Abha, in the Eastern Province, or in Riyadh and Buraidah were rarely, if ever, relayed. The approach developed by foreign media on Saudi women made difficult the circulation of alternative images when they showed women whose faces were covered, who mobilized en masse, who did not focus on ostensibly women`s causes, and who may be of non-middle class status. This discrepancy speaks to a particular construction of Saudi women’s victimhood in the Western imaginary and of what counts as liberatory politics. This perhaps unintended practice of censorship is engendered through a representational framework that insists on: (1) the collective victimhood of Saudi women as women and only as women, ignoring other dimensions of possible oppression and struggle; (2) the successful (visible) individualized woman as being the sole carrier of political agency; and (3) the projection of a liberal vision of women’s empowerment as the standard for what is liberatory.

This is where this politics of representation and surveillance meet. The politics of representation have made "exceptional women" hyper visible while excluding other images of women in Saudi Arabia—poor, non-national women, non-liberal women, women who insist on their public anonymity—even when they have acted with the explicit purpose of making their actions visible and their voices heard. The Saudi state has worked to make all inhabitants—Saudis and non-national residents, women and men—increasingly visible in particular ways, i.e. under scrutiny: this visibility allows for new forms of control, rather than expanded freedom. While the surveillance state becomes increasingly powerful and the control over images increasingly restrictive, it seems that the communication strategy of the Saudi state has been an effective tool in rendering invisible the activists who tried to escape it.

References

Abu Lughod, Lila, 1998. Remaking Women. Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ahmed, Leila, 1992. Women and Gender in Islam: historical roots of a modern debate, Yale University Press.

Al-Rasheed, Madawi, 2013. A Most Masculine State. Gender, Politics, and Religion in Saudi Arabia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dakhlia, Jocelyne, 2007. « Harem : ce que les femmes, recluses, font entre elles », Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, 26, URL : http://clio.revues.org/5623.

Le Renard, Amélie, 2011. Femmes et espaces publics en Arabie Saoudite. Paris: Dalloz.

Le Renard, Amélie, 2014. A Society of Young Women. Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi Arabia. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Puar, Jasbir, 2012 (2007). Homonationalisme: politiques queers après le 11 septembre. Paris: Amsterdam.

[1] There are different accessories used to cover one’s face in Saudi Arabia, called niqab, burqa‘ and litham.

[2] The material quoted here was produced and published in France, where I followed the media more closely. While there is a specific French history of “unveiling Muslim women,” the representations described convey discourses on Saudi women that are not limited to French media.

[3] I prefer not to identify them by name, because doing so would seem to implicate a few women in the process, when my contention is that the regime and foreign media co-produce the image of these “exceptional women.” My intention is not to undermine these women and their contributions.

[4] On texts produced since the sixteenth century by Orientalists, see Dakhlia, Jocelyne, 2007. “Harem : ce que les femmes, recluses, font entre elles,” Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, 26, URL : http://clio.revues.org/5623. On representations in the United States of Middle Eastern subjects as sexually deviant see Puar, Jasbir, 2012 (2007). Homonationalisme: politiques queers après le 11 septembre. Paris: Amsterdam.

[5] The two caricatures were published in a satirical newspaper and a magazine with very different political lines. See “Un zoo féminin dans le désert saoudien” [A female zoo in the Saudi desert], Charlie Hebdo, August 22, 2012, and “Arabie Saoudite. Bientôt une ville réservée aux femmes... pour les émanciper,” [Coming soon to Saudi Arabia: A Women-only City… to liberate them], Causette, n°27, September, 2012.

[6] “Arabie: le roi de la lingerie au pays du voile,” [Arabia : the king of lingerie in the country of the veil] broadcasted on M6, 20 March 2011.

[7] There have been many cases of impersonation in trials that involve women and their legal guardians, whereby the latter brought a different woman not involved in the case, and the niqab prevented the judge from identifying the fraudulent practice.

[9] In 2013 and 2014 several Saudi citizens were arrested or sentenced to prison after posting on social media videos of anti-government demonstrations, or videos criticizing the regime. See http://tinyurl.com/ng9ddc6 (Accessed November 17, 2014) and "Arrest of Saudi netizens triggers Twitter, YouTube closure fears", BBC Monitoring (3 April 2014).

[10] For instance, it is now impossible to recharge a mobile phone without giving one’s ID number. In practice, this means that the mobile phone holder is known by the company, which collaborates with state security.

![[Image by Rana Jarbou.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Monaarticlephoto.jpg)